On Harold Klunder's Then And Now

21 November - 11 January, 2025

Around 2001, Harold Klunder had what turned out to be his last solo show at Sable-Castelli, the fabled underground lair of Jared Sable. His gallery had been one of the top spaces in Canada for decades but in his senior years a cloud of inertia seemed to have formed around Sable and many artists consequently left. He abruptly closed his gallery soon afterwards, turning off the lights on a long and storied run of post-war contemporary art dealing in Toronto. I was the curator of a regional Ontario museum at the time and I saw Harold's show on its closing Saturday. Most of the paintings had sold. But one that I liked hadn't and I asked Jared about buying it. I sheepishly said I would have to make payments. He looked at me like being poor was among the more distasteful things you could be in life, but finally agreed. I asked him when we could arrange delivery. It was almost 5pm. Jared said, just take it off the wall. I had never agreed to spend that much money on art before so I found his waving-away gesture a bit deflating. No congrats on your acquisition. No handshake. No wrapping, in fact. I walked through Yorkville with the painting under my arm and the next day sent Harold a note to tell him how pleased I was. He was flattered and very kind.

Having shown with Sable for 27 years, Harold wanted to take his time, out of respect, before showing again anywhere in Toronto. When I was about to launch CRG in 2003 I reached out to begin a conversation. Harold came by the gallery and I think part of him found the old wood floor, the big storefront window on Queen West with the sun streaming in, the high tin ceiling, all of it refreshing after Sable's polished, subterranean gallery. Harold had his first solo with me in 2004 and it went well, everything sold and we got a half-page in the Globe. I was so grateful for his trust because, really, he could have shown anywhere in Toronto. Olga's cavernous space would have been such a natural fit. But we worked well together and I enjoyed his calm, gentle company. Studio visits to Flesherton and Montreal were as immersive as his paintings were. Now twenty years have passed since that first show, Harold's paintings are in every Canadian museum, from the VAG to the National to the AGNS, and Harold, at 81, is still painting with the same compulsion as the gangly teenager he was in 1962 when he painted the earliest work in this new show, Then And Now. I am grateful that things have worked out that I can provide much more space now than I was able to then on Queen, but still it's not enough. The show is purposely overhung (something I've studiously avoided since the beginning…) but it is overhung out of reverence. Reverence for Harold's dedication, for the materiality of the paint, and for the many ways Harold puts it down. Gary Michael Dault wrote that Harold's paintings "beggar language," meaning they tend to hit the subconscious before anything verbal can be articulated. In that regard, although the vast majority of Harold's paintings are labelled Self-Portraits, they are not often meant as physical likeness, but rather as evocations of interior states of being, like CT scans of an artist's emotional life as its chapters unfold through thick and thin. The first big painting you encounter in the show is Sacred And Profane Love (Self-Portrait III) from 1985-1986. Shot through with gnarled, turbulent episodes of violent thick paint, there remains none of the sumptuous, organized calm of Titian's version from 1514. Instead comes the urgency that characterized much of CoBrA's work from 1950. With Dutch origins (like Klunder), the CoBrA group argued for "Creation before theory; that art must have roots; materialism which begins with the material; the mark as a sign of wellbeing, spontaneity, experimentation: it was the simultaneity of these elements which created CoBrA."

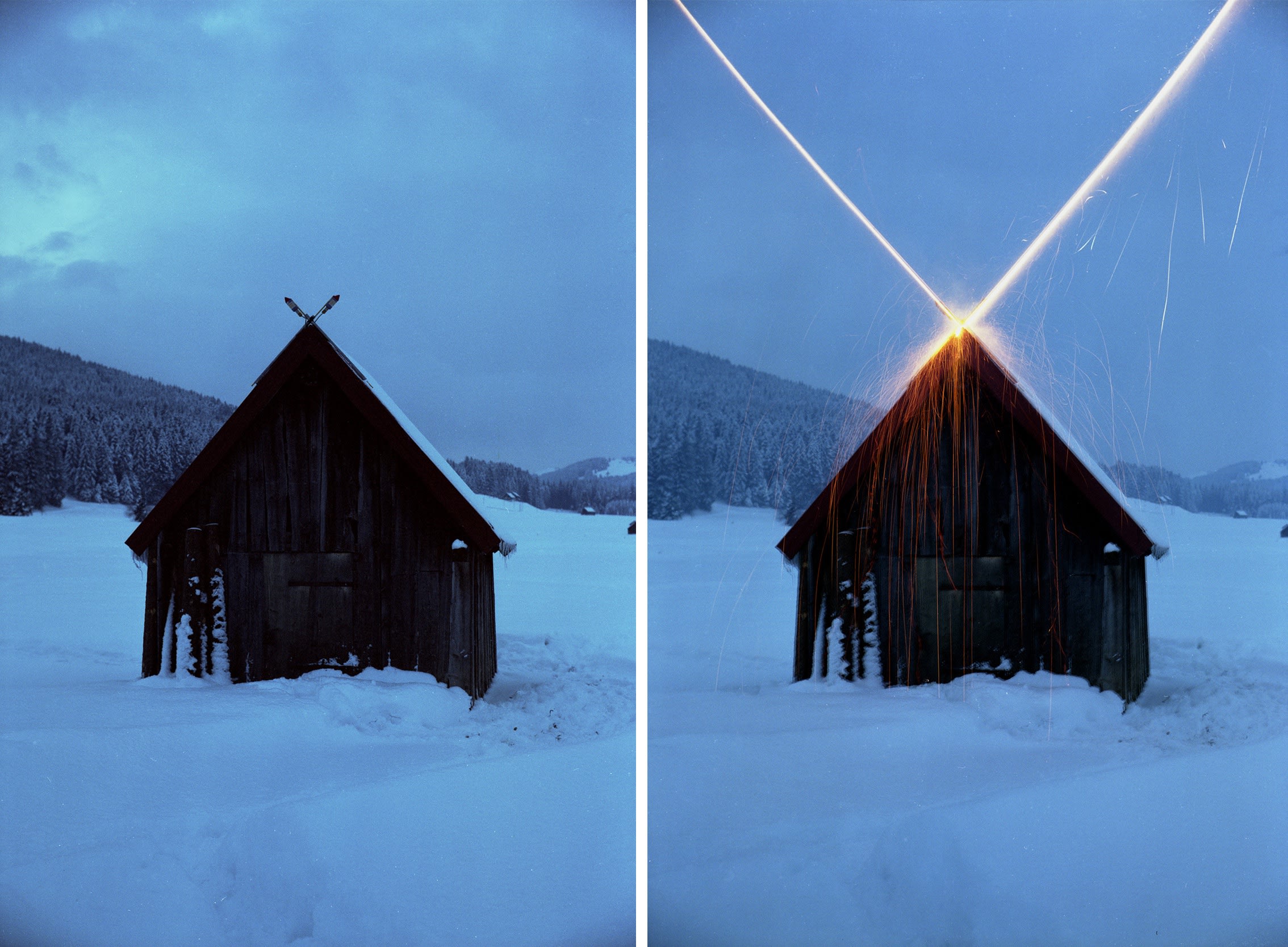

To the right of the love that is both sacred and profane is a large, new diptych, itself hung over top of the mural Harold painted on the wall for his 2018 show. The diptych is titled Nessun Dorma ("none shall sleep"), the famous aria from the final act of Puccini's opera Turandot. "Vanish, oh night! Set, you stars! At dawn I will win!". We can imagine the painter, up late working alone, parrying with the canvas, building up gestures on gestures, solving a riddle. This diptych with its earthy hieroglyphics, reminds me of Paul Klee. The white flashes suggest a constellation gleaming through an impenetrable night. Frank Auerbach, the British-German painter that Harold deeply admired who died November 11th, once said, It seems to me madness to wake up in the morning and do something other than paint, considering that one may not wake up the following morning.

So it is with Klunder, painting comes first. To the left of None Shall Sleep is a strange, desert-like work, Little Egypt (The Quest For Certainty) from 1997 - 1998. An eye, appraising and alert, looks down on a cellular scene. A cartoon pyramid, painted like Guston might, looms on the horizon across from a pink portal. In between, a band of blue-purple, like the Red Sea, defines the middle. Harold has said that he makes paintings that he wants to look at, that he hasn't seen elsewhere. This eye conjures up a primordial being, perhaps the way a sea creature eyed up the beckoning shore 365 million years ago and envisioned a new life on land. Around the corner is the small 1962 abstraction painted when Harold was 19, halfway through his art education at Central Tech in Toronto. Borduas had died in Paris just two years prior and in 1962 a posthumous retrospective that originated at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts traveled to the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Toronto. What I mean is, the atmosphere of post-war abstraction was thick in the air for the young Klunder then and it follows that he would have been enthralled by the freedom of its possibilities. But the biomorphic, Arp-like, quasi-figurative vocabulary of forms that Harold eventually became very well known for did not truly begin to surface until the early 80s (the 70s mostly given over to exploring the rising prominence of fast-drying acrylic paint).

Then And Now is anchored in the main gallery by Harold's magisterial, eighteen-foot triptych from 1986-87, Future, Present, Past (self-portrait). A blazing, molten, writhing journey that seems half oil paint, half solar flare, each panel a tectonic plate slowly crushing into its other. The many passages of bravura paint-handling reveal no hesitation, an impastoed story of time unfolding in fluid, back and forth waves of dynamic energy. Over the many decades that Harold has been painting his work has gone in and out of fashion and yet he presses on, untroubled, moving through time, true to his singular vision. A personal vision that is nevertheless tethered to a deep understanding of art history generally and of other Dutch painters in particular (Rembrandt, de Kooning, Van Gogh, Vermeer…) but also painters as varied as Rogier van der Weyden, El Greco, Leon Kossoff, Munch and Ensor. To the left of Future, Present, Past we find a quite different work, a thinly painted seven foot square oil on linen, one of a suite of four called Language And Music. The title refers to Klunder's interest in brain activity when subjected to stimuli such as the human voice and the effect of music. Made with impressive restraint, here Klunder evokes a glitchy narrative between the central figure and the architecture of the background. The painting is hung adjacent to Future, Present, Past for the manner in which Klunder presents the central figure with two after-images trailing behind it, flashes of time's arrow. The architecture framing Klunder's figure recall the tubular cages that Francis Bacon used to such strong effect in his own portrayal of figures in ambiguous settings. To the left of this painting is a masterpiece, Sun And Moon, from the mid-90s, one of Harold's strongest periods. Here the paint coalesces around a thick, black, coagulating cellular structure in the middle, an event that seems about to divide and complexify, floating over a hastily painted, brushed-in background of ochres and rusty yellows. Arshile Gorky's landscapes from 1943 come to mind (the year Klunder was born, in Deventer, The Netherlands), as do the brown winter fields of the family farm in Holland, from which the Klunders left in 1952 to come to Canada, sailing to Halifax, taking the train to Montreal where they froze and didn't speak French, to eventually re-establishing themselves on an Ontario farm, one that Harold took pains not to have to return to after completing his studies in Toronto in 1964, when Yorkville was the beatnik opposite of the posh enclave it is now. Encrusted in paint the colour of dried mud, a portrait emerges at bottom left, born of the ground. Harold once said in an interview that "painting is like tilling the earth, listening to the rhythm of the seasons, the pulse of life itself." The farm, it seems, never leaves you. And it is true that throughout Klunder's painting practice his gestures seem to have geological, biological, chrysalis-like roots, of oozing shapes on shapes, each on their way to becoming something else as the viewer allows the painting to unfold. There is a durational aspect to Harold's work: invariably there are two dates on his paintings, no matter how small the work: the year he began and the year of its completion. Harold hopes for the same dedication in his viewers: completing the painting by letting it reveal itself episodically over time.

Now we arrive at Want And Destiny from 2007 - 2009. This is a fully resolved painting, an iconic Klunder, roiling with an energy that seems to coil around an almost planetary central axis, set amid a deep, murky ground. At top left the best egg yolk sun. The painting is also notable for its alluring passages of bright green, a relatively rare colour for Klunder to deploy. Then, of course, the faces and figures coyly announce themselves after the force of the all-over abstraction relents for a moment. A totemic figure flanks each side and a strong portrait holds the centre. When this painting was shown in the window at CRG on Queen the private dealer Chris Varley came and saw it. Then he called his clients and said, I am standing in front of a painting so good it will curl your toes. You must get it, or I will.

They did.

As we get to the east wall, a very small, potent oil on burlap painted in a Brooklyn studio Harold once kept. A head is enshrouded in the weave of the background while three orbs of colour glow forth. To its left comes the big Rooted In Earth (The Sound Of The Moth), a seven-foot slab of blue-black virtuosity, the interplay of forms and colours vibrating in harmonious dialogue. Harold has said, I have a preoccupation with, in a sense, seeing the painting as a mirror, and as I look at the painting it looks at me, and there's this sense of working with something that I can intimately understand, full of secrets that other people don't know, or it's a life that I can present because I know myself differently than anybody else would know me, so there's vulnerability that appeals to me…

Finally we come to the north wall, a dark wall of four works united in their chthonic force. Chthonic meaning 'in, under or beneath the earth.' Or perhaps they are figures born at twilight, crepuscular forms. Vespertine. That which flourishes in the evening. The bluest work, at far right, reads like a fever dream, of visitations by scarlet red figures. Beside it comes Skirts Of The Forest. Here, through black masses of trees, a pagan ceremony is underway? Something is afoot. Luminous shapes abound, shadowy events. To its left, a brooding triptych, a head rearing up in the centre of each. James Campbell, who has written well and often on Harold's work, wrote: 'Merleau-Ponty said, "The painter 'brings his body with him,' says Valery. Indeed we cannot imagine how a mind could paint." This is a truism particularly where Klunder's paintings are concerned, for they are, above all, bodied spaces, phenomenal fields, matrices of corporeal performances.'

Last there remains one small, dark diptych, tucked in the northwest corner, absorbing the radiant orange heat and light coming off the monumental 1987 triptych adjacent to it. That little diptych I leave for you to engage with. We can bring to painting as much as it brings to us, receptive to its mysterious language or not, perhaps depending on the day or one's mood. When I built the gallery on St Helen's I purposely inserted an angled wall in the front space as a kind of obstacle to the approach of the main gallery in the back. Much like the ramp at the National Gallery, the idea was to give pause, to create a breathing moment between life and art, to let whatever the day outside had thus far wrought upon you be now laid down and left there, if only for the duration of the viewing to come. Everyone carries their own bag of rocks. To engage with a painting is first to be present with it, to agree to give it our attention, that most coveted and fought over thing today - our attention - and if we can do that with a painting then the moment begins, becomes fuller, and then the reveries come next, mental digressions, recollections and connections sparked by the image before us, brought on by a painter mixing pigment and oil and laying it down on a scrap of burlap, coaxing forth realms.

Thank you for seeing this show, and thank you Harold Klunder for your work.

- CR

21 November - 11 January, 2025

Around 2001, Harold Klunder had what turned out to be his last solo show at Sable-Castelli, the fabled underground lair of Jared Sable. His gallery had been one of the top spaces in Canada for decades but in his senior years a cloud of inertia seemed to have formed around Sable and many artists consequently left. He abruptly closed his gallery soon afterwards, turning off the lights on a long and storied run of post-war contemporary art dealing in Toronto. I was the curator of a regional Ontario museum at the time and I saw Harold's show on its closing Saturday. Most of the paintings had sold. But one that I liked hadn't and I asked Jared about buying it. I sheepishly said I would have to make payments. He looked at me like being poor was among the more distasteful things you could be in life, but finally agreed. I asked him when we could arrange delivery. It was almost 5pm. Jared said, just take it off the wall. I had never agreed to spend that much money on art before so I found his waving-away gesture a bit deflating. No congrats on your acquisition. No handshake. No wrapping, in fact. I walked through Yorkville with the painting under my arm and the next day sent Harold a note to tell him how pleased I was. He was flattered and very kind.

Having shown with Sable for 27 years, Harold wanted to take his time, out of respect, before showing again anywhere in Toronto. When I was about to launch CRG in 2003 I reached out to begin a conversation. Harold came by the gallery and I think part of him found the old wood floor, the big storefront window on Queen West with the sun streaming in, the high tin ceiling, all of it refreshing after Sable's polished, subterranean gallery. Harold had his first solo with me in 2004 and it went well, everything sold and we got a half-page in the Globe. I was so grateful for his trust because, really, he could have shown anywhere in Toronto. Olga's cavernous space would have been such a natural fit. But we worked well together and I enjoyed his calm, gentle company. Studio visits to Flesherton and Montreal were as immersive as his paintings were. Now twenty years have passed since that first show, Harold's paintings are in every Canadian museum, from the VAG to the National to the AGNS, and Harold, at 81, is still painting with the same compulsion as the gangly teenager he was in 1962 when he painted the earliest work in this new show, Then And Now. I am grateful that things have worked out that I can provide much more space now than I was able to then on Queen, but still it's not enough. The show is purposely overhung (something I've studiously avoided since the beginning…) but it is overhung out of reverence. Reverence for Harold's dedication, for the materiality of the paint, and for the many ways Harold puts it down. Gary Michael Dault wrote that Harold's paintings "beggar language," meaning they tend to hit the subconscious before anything verbal can be articulated. In that regard, although the vast majority of Harold's paintings are labelled Self-Portraits, they are not often meant as physical likeness, but rather as evocations of interior states of being, like CT scans of an artist's emotional life as its chapters unfold through thick and thin. The first big painting you encounter in the show is Sacred And Profane Love (Self-Portrait III) from 1985-1986. Shot through with gnarled, turbulent episodes of violent thick paint, there remains none of the sumptuous, organized calm of Titian's version from 1514. Instead comes the urgency that characterized much of CoBrA's work from 1950. With Dutch origins (like Klunder), the CoBrA group argued for "Creation before theory; that art must have roots; materialism which begins with the material; the mark as a sign of wellbeing, spontaneity, experimentation: it was the simultaneity of these elements which created CoBrA."

To the right of the love that is both sacred and profane is a large, new diptych, itself hung over top of the mural Harold painted on the wall for his 2018 show. The diptych is titled Nessun Dorma ("none shall sleep"), the famous aria from the final act of Puccini's opera Turandot. "Vanish, oh night! Set, you stars! At dawn I will win!". We can imagine the painter, up late working alone, parrying with the canvas, building up gestures on gestures, solving a riddle. This diptych with its earthy hieroglyphics, reminds me of Paul Klee. The white flashes suggest a constellation gleaming through an impenetrable night. Frank Auerbach, the British-German painter that Harold deeply admired who died November 11th, once said, It seems to me madness to wake up in the morning and do something other than paint, considering that one may not wake up the following morning.

So it is with Klunder, painting comes first. To the left of None Shall Sleep is a strange, desert-like work, Little Egypt (The Quest For Certainty) from 1997 - 1998. An eye, appraising and alert, looks down on a cellular scene. A cartoon pyramid, painted like Guston might, looms on the horizon across from a pink portal. In between, a band of blue-purple, like the Red Sea, defines the middle. Harold has said that he makes paintings that he wants to look at, that he hasn't seen elsewhere. This eye conjures up a primordial being, perhaps the way a sea creature eyed up the beckoning shore 365 million years ago and envisioned a new life on land. Around the corner is the small 1962 abstraction painted when Harold was 19, halfway through his art education at Central Tech in Toronto. Borduas had died in Paris just two years prior and in 1962 a posthumous retrospective that originated at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts traveled to the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Toronto. What I mean is, the atmosphere of post-war abstraction was thick in the air for the young Klunder then and it follows that he would have been enthralled by the freedom of its possibilities. But the biomorphic, Arp-like, quasi-figurative vocabulary of forms that Harold eventually became very well known for did not truly begin to surface until the early 80s (the 70s mostly given over to exploring the rising prominence of fast-drying acrylic paint).

Then And Now is anchored in the main gallery by Harold's magisterial, eighteen-foot triptych from 1986-87, Future, Present, Past (self-portrait). A blazing, molten, writhing journey that seems half oil paint, half solar flare, each panel a tectonic plate slowly crushing into its other. The many passages of bravura paint-handling reveal no hesitation, an impastoed story of time unfolding in fluid, back and forth waves of dynamic energy. Over the many decades that Harold has been painting his work has gone in and out of fashion and yet he presses on, untroubled, moving through time, true to his singular vision. A personal vision that is nevertheless tethered to a deep understanding of art history generally and of other Dutch painters in particular (Rembrandt, de Kooning, Van Gogh, Vermeer…) but also painters as varied as Rogier van der Weyden, El Greco, Leon Kossoff, Munch and Ensor. To the left of Future, Present, Past we find a quite different work, a thinly painted seven foot square oil on linen, one of a suite of four called Language And Music. The title refers to Klunder's interest in brain activity when subjected to stimuli such as the human voice and the effect of music. Made with impressive restraint, here Klunder evokes a glitchy narrative between the central figure and the architecture of the background. The painting is hung adjacent to Future, Present, Past for the manner in which Klunder presents the central figure with two after-images trailing behind it, flashes of time's arrow. The architecture framing Klunder's figure recall the tubular cages that Francis Bacon used to such strong effect in his own portrayal of figures in ambiguous settings. To the left of this painting is a masterpiece, Sun And Moon, from the mid-90s, one of Harold's strongest periods. Here the paint coalesces around a thick, black, coagulating cellular structure in the middle, an event that seems about to divide and complexify, floating over a hastily painted, brushed-in background of ochres and rusty yellows. Arshile Gorky's landscapes from 1943 come to mind (the year Klunder was born, in Deventer, The Netherlands), as do the brown winter fields of the family farm in Holland, from which the Klunders left in 1952 to come to Canada, sailing to Halifax, taking the train to Montreal where they froze and didn't speak French, to eventually re-establishing themselves on an Ontario farm, one that Harold took pains not to have to return to after completing his studies in Toronto in 1964, when Yorkville was the beatnik opposite of the posh enclave it is now. Encrusted in paint the colour of dried mud, a portrait emerges at bottom left, born of the ground. Harold once said in an interview that "painting is like tilling the earth, listening to the rhythm of the seasons, the pulse of life itself." The farm, it seems, never leaves you. And it is true that throughout Klunder's painting practice his gestures seem to have geological, biological, chrysalis-like roots, of oozing shapes on shapes, each on their way to becoming something else as the viewer allows the painting to unfold. There is a durational aspect to Harold's work: invariably there are two dates on his paintings, no matter how small the work: the year he began and the year of its completion. Harold hopes for the same dedication in his viewers: completing the painting by letting it reveal itself episodically over time.

Now we arrive at Want And Destiny from 2007 - 2009. This is a fully resolved painting, an iconic Klunder, roiling with an energy that seems to coil around an almost planetary central axis, set amid a deep, murky ground. At top left the best egg yolk sun. The painting is also notable for its alluring passages of bright green, a relatively rare colour for Klunder to deploy. Then, of course, the faces and figures coyly announce themselves after the force of the all-over abstraction relents for a moment. A totemic figure flanks each side and a strong portrait holds the centre. When this painting was shown in the window at CRG on Queen the private dealer Chris Varley came and saw it. Then he called his clients and said, I am standing in front of a painting so good it will curl your toes. You must get it, or I will.

They did.

As we get to the east wall, a very small, potent oil on burlap painted in a Brooklyn studio Harold once kept. A head is enshrouded in the weave of the background while three orbs of colour glow forth. To its left comes the big Rooted In Earth (The Sound Of The Moth), a seven-foot slab of blue-black virtuosity, the interplay of forms and colours vibrating in harmonious dialogue. Harold has said, I have a preoccupation with, in a sense, seeing the painting as a mirror, and as I look at the painting it looks at me, and there's this sense of working with something that I can intimately understand, full of secrets that other people don't know, or it's a life that I can present because I know myself differently than anybody else would know me, so there's vulnerability that appeals to me…

Finally we come to the north wall, a dark wall of four works united in their chthonic force. Chthonic meaning 'in, under or beneath the earth.' Or perhaps they are figures born at twilight, crepuscular forms. Vespertine. That which flourishes in the evening. The bluest work, at far right, reads like a fever dream, of visitations by scarlet red figures. Beside it comes Skirts Of The Forest. Here, through black masses of trees, a pagan ceremony is underway? Something is afoot. Luminous shapes abound, shadowy events. To its left, a brooding triptych, a head rearing up in the centre of each. James Campbell, who has written well and often on Harold's work, wrote: 'Merleau-Ponty said, "The painter 'brings his body with him,' says Valery. Indeed we cannot imagine how a mind could paint." This is a truism particularly where Klunder's paintings are concerned, for they are, above all, bodied spaces, phenomenal fields, matrices of corporeal performances.'

Last there remains one small, dark diptych, tucked in the northwest corner, absorbing the radiant orange heat and light coming off the monumental 1987 triptych adjacent to it. That little diptych I leave for you to engage with. We can bring to painting as much as it brings to us, receptive to its mysterious language or not, perhaps depending on the day or one's mood. When I built the gallery on St Helen's I purposely inserted an angled wall in the front space as a kind of obstacle to the approach of the main gallery in the back. Much like the ramp at the National Gallery, the idea was to give pause, to create a breathing moment between life and art, to let whatever the day outside had thus far wrought upon you be now laid down and left there, if only for the duration of the viewing to come. Everyone carries their own bag of rocks. To engage with a painting is first to be present with it, to agree to give it our attention, that most coveted and fought over thing today - our attention - and if we can do that with a painting then the moment begins, becomes fuller, and then the reveries come next, mental digressions, recollections and connections sparked by the image before us, brought on by a painter mixing pigment and oil and laying it down on a scrap of burlap, coaxing forth realms.

Thank you for seeing this show, and thank you Harold Klunder for your work.

- CR