"I can only conclude that the acceptance and presence of death in Mora's photographs make them compelling. There's a rapt tension between the tranquillity of the landscapes

and the instability of where they were taken. In other words, between life and death. This dichotomy is presented subtly, without fear. The result is transcendent and otherworldly.

"I grew up Catholic, believing that God is watching me from above the clouds," said Mora. "In Catholicism, it is believed that when we die, our soul flies up above the clouds. If you are good, you go to heaven, depicted as a place full of clouds," he continued. The awe-inspiring landscapes contain a uni- versal experience: gazing out a window and being in awe of what lies outside of it to the point that your ego shrinks down to a manageable form (for the duration of the trip, at least)." - excerpt from a text by Tatum Dooley

FLYING HIGH

By Tatum Dooley

Air travel is a kind of purgatory. Between your destination and starting point, you hover in an in-between state. Who you are and what you do are similarly untethered. In the air, you can shed all responsibilities and simply exist. There are no conversations that need to be had or phone calls to make-your only obligations are to watch a movie or two, stare out the window, and think.

There are two types of people who travel: those who prefer the aisle seat (prioritizing comfort and movement, ease of access to the washroom) and those who prefer the window seat (opting for aesthetics and wonder, the ability to see the world from a new vantage point). Luis Mora is very much in the latter category. During travels for work, Mora began documenting the view from plane windows. On each flight, he takes thousands of photographs, capturing the terrain between Toronto and Los Angeles, London and Toronto, and Toronto to Colombia, where his previous series of photo- graphs, Say It With Flowers, were taken. The photographs in Window Seat, taken between 2018 and 2024, represent a transient state between destinations, capturing a universal feeling of being adrift, a physical location that mirrors an emotional state.

Every time I fly, I'm taken with how unnatural the act is. I feel close to death and uncomfortable-how does the airplane work? What mechanics keep the machine in the air? What will I leave behind? I'm full of equal parts fear and awe. I grit my teeth and watch my progress on the tiny screen, counting down the minutes until my feet are on solid ground. On the other hand, Mora embraces the discomfort of being con- fronted with his own mortality. "I think about death every single time I fly, and I often cry. I find a comfortable feeling in the thought that maybe I am going to die today, and I am okay with it," he says. Mora's photographs tug me towards a new perspective, urging me to no longer be afraid but instead accept the beauty of life, even if it means death. Mora's photographs ask: What other way is there to live? When I wrote about Mora's previous photographs in 2019, Say It With Flowers, my mind similarly wandered towards death. "It feels potent that Mora chooses to focus so acutely on the flowers' brief life at the Paloquemao market-when they're not only in between life and death, a state of purgatory, but also floating between homes," I wrote. It's note-worthy, forgetting the lines I wrote previously, that I came to the same conclusion about the presence of purgatory and death in Window Seat.

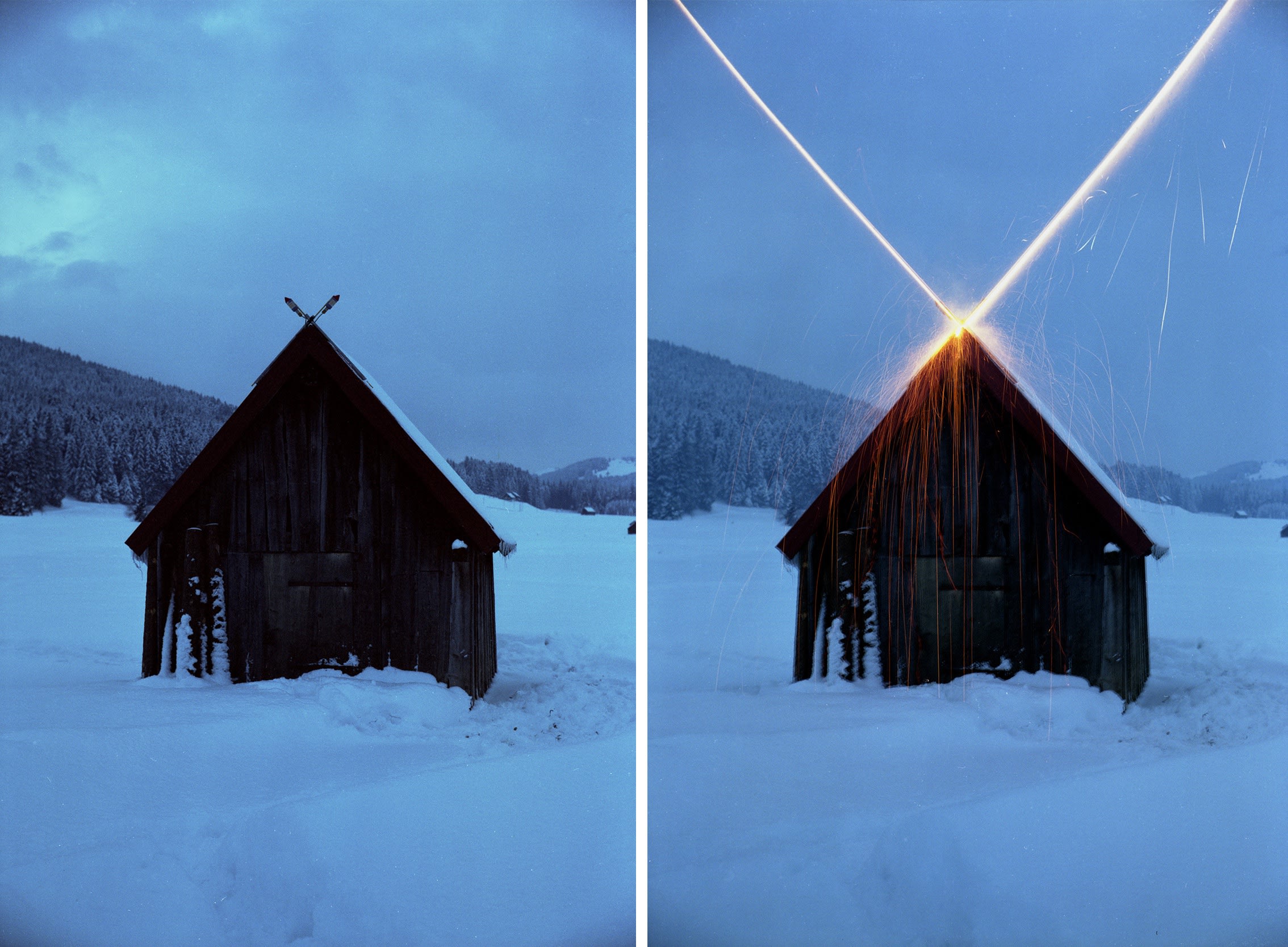

I can only conclude that the acceptance and presence of death in Mora's photographs make them compelling. There's a rapt tension between the tranquillity of the landscapes

and the instability of where they were taken. In other words, between life and death. This dichotomy is presented subtly, without fear. The result is transcendent and otherworldly.

"I grew up Catholic, believing that God is watching me from above the clouds," said Mora. "In Catholicism, it is believed that when we die, our soul flies up above the clouds. If you are good, you go to heaven, depicted as a place full of clouds," he continued. The awe-inspiring landscapes contain a uni- versal experience: gazing out a window and being in awe of what lies outside of it to the point that your ego shrinks down to a manageable form (for the duration of the trip, at least).

The history of the landscape is typically relegated to paint- ing-horizontal representations of the natural world. Mora forgoes the typical composition, turning it on its side and shooting vertically. The portrait landscape nicely replicates the iconic oval shape of an airplane window. Although it is never present in Mora's photographs, the shape is inferred. The choice to shoot this series vertically makes sense; it's the only way to view a landscape from a plane. The vantage point is a unique combination of a severe angle and a nearby horizon line. Yet the width of the landscape is expansive and constantly changing due to the plane's movement. This means the moment is already gone as soon as you take a photograph. Mora's photographs are impossible to recreate- the exact weather conditions, time of day, year, and coordin- ates-all coming together to create a one-of-a-kind memory with infinite possibilities. Each moment is rarer than the next.

Aerial photography is part of the art history canon. The first photograph ever taken is a heliograph made by Joseph- Nicéphor Niépce in 1826 of a rooftop in France. Taken through a window, the viewer can make out trees, rooftops, and a far- away landscape in a grainy form. During World War II, photographer Edward Steichen took numerous images from airplanes, the ravages of war turned into abstract compositions of crops, roads, and terrain. Perhaps the most famous photograph ever taken is of the earth taken from the moon by astronaut William Anders during the Apollo 8 mission. There is a human impulse to view ourselves from a bird's eye-to understand and see concretely that we are part of something larger than ourselves.

The average altitude that commercial airlines fly is 35,000 feet. Aerial photographs are taken in brief moments in time; we can't stay suspended in flight forever. We go up and want to remember the view and the novel feeling of being above the earth. When I fly, I'm often overcome with the impulse to take a photo. With my iPhone, I reach over the person sitting next to me to snap a sunset or the beauty of clouds seen from above. The result typically lacks the gravitas of the moment. Not with Mora's photographs. Mora captures something ungraspable. The cropping and highly pigmented colours in Window Seat replicate the awe of looking out the window

and seeing something unreal.

How the photographs in Window Seat are printed, glossy and smooth, replicates the condition in which they were taken. When looking at the series in person, the viewer can see glimpses of themselves in the photographs, not unlike how we can see ourselves in the glass of a window. This acci- dental double exposure adds another layer to the pieces. It asks: Where do we fit into the world? How can the individual merge with the universal?

To take a photograph through a window is to view the world through someone else's eyes. When looking through Mora's eyes, the viewer is rewarded with a world that is vibrant and humming with energy. Flying provides perspective on life. Confronted with the possibility of death and given a new visual perspective on the world, looking out an airplane window begets humility and wonder. Mora translates these feelings into photographs that are equally familiar and awe-inspiring-just as life is.